Category Archives: Features

Grinding it Out

Already, 2013 has been an impressive year for Corridor Sausage. The artisan sausage company has found a rhythm in their new Eastern Market facility, they’ve launched The Grindhouse food truck, and thanks to USDA approval, they’re about to start selling to retail outlets.

So it seems like this is the time to take the region by storm.

Corridor co-founder Will Branch agrees. “If it isn’t, I probably have a bankruptcy and a divorce in my future,” he says with a hearty laugh. He’s kidding (sort of), but after a long three and a half years of strenuous work, he and partner Zak Alexander seem poised to truly reap the fruits of their labor.

The journey began in 2009 when Branch and Alexander were cooking together at a southeast Michigan restaurant. Neither wanted to open their own eatery, but both were excited at the prospect of something beyond working the line. “If I wasn’t going to law school and I was going to cook, it wasn’t to work for someone else for the rest of my life,” Branch says. “It’s about ‘what am I going to create?'”

Branch had grown up as a routine visitor to metro Detroit’s ethnic butchers, and Alexander had worked on a charcuterie program at Novi-based Steve & Rocky’s prior to their meeting. So the notion of starting a sausage business emerged quickly. “Planning a sausage or charcuterie shop is something every cook or chef talks about at 2am after too much Jameson and Guinness,” Branch jokes.

Wasting little time, they organized a meeting with some potential investors, a restaurant group looking to put a few businesses into a Midtown, Detroit-based development.

“That’s where we started to get attached to the space in the Cass Corridor,” Branch notes. Schoolcraft College generously granted them one-time use of their space and equipment to put together a product tasting, and though it went well and lease negotiations proceeded swiftly, the project eventually stalled. “We branded as Corridor Sausage and thought it was a done deal,” he continues, “And you could say, ‘Oh man, that didn’t come through, we’re bitter about it,’ but we’re not. Those people were all so, so helpful.”

The duo, unfazed, took a flexible approach, looking for any entry point to the marketplace.

They acquired rental space in Howell, got licensed, and started making sausage just seven or eight hours a week. For a full year, they made sausage to order, serving clients like Woodbridge Pub and Jolly Pumpkin. That slow ascent allowed them to perfect their process, eventually making about 500 pounds of sausage in just their eight hour kitchen stint, which opened the door to farmer’s markets.

Jolly Pumpkin’s first order, which they made on Labor Day, 2009, still stands as a memorable moment. They had to produce 250 pounds, and they weren’t yet operational in Howell. So they borrowed restaurant space in Detroit with coolers in the basement, grinders on the fourth floor, and stuffers on the first floor. Branch’s exhaustion is evident in his voice, even years later.

But looking back, he couldn’t be happier. “Pretty much, [the Jolly Pumpkin] order financed our company,” he contends. “Instead of going out of pocket, we had something sitting in our bank account we could parlay into success.” And he still remembers what they put together that day – Vietnamese chicken, lamb merguez, apple and sage pork, and Moroccan lamb with fig.

In summer of 2012, they moved into their new production facility in Eastern Market, a space at the corner of Division and Orleans – perhaps best known to Market goers as the Marry Me Tizzie building. With the new space came new equipment as well, including a vacuum stuffer than apportions the ground meat into their desired quantity. For all its obvious advantages, that brought a series of headaches all its own.

Branch explains: “That first month in the new space sucked. It was awful. It was new equipment, it was an enormous space compared to what we were used to. So everything took longer…. Eight months ago, a fuse blew on our stuffer. Now we know how to fix it and what to look for, but at the time… I didn’t know.” After wading through circuit boards and wires, they got the machine repaired – and now they’re capable of producing thousands of pounds per week.

In outlining that production process, Branch and Alexander humbly reveal the level of quality to which they aspire.

On Mondays, their sole task is preparing the ingredients to mix into the meat – chopping fresh herbs, mincing fresh garlic, weighing spices and figs, and prepping sauces. There are no bagged mixes, no pre-assembled products that go into their sausage. Tuesday, I watched them halve chunks of lamb and unpack ethically raised pork to head into the grinder. After grinding, they mix with their prepped ingredients and stuff into natural casings. And finally, on Wednesday, they package and freeze the meat.

USDA certification represents the next evolution: For Corridor, the rules will preclude any possibility of working with the same protein on the same day. Thus, different meats will get moved to different days of the week, meaning their production schedule must expand. “Right now, we typically make four to six varieties, 600 to 800 pounds [on that Tuesday],” Branch says. “We’ll have to shift our production model to maybe 1,000 to 1,500 pounds in a day, but that’s maybe only two varieties.”

If it seems like a lot of effort, that’s because it is. As finely honed as their process is, it still takes hours of focused effort to achieve. After all this time, Branch still enjoys talking about it. And when I ask what makes his sausage different, he laughs, “It’s the love. The secret ingredient.”

Earnestly, he continues, “No, it’s the quality and the care we put into it. The freshness of the meats. A lot of it is the recipes, the flavor that comes through you won’t get anywhere else.”

Early on, Corridor routinely extended their business to regional catering. Indeed, Branch credits a spike in their initial Eastern Market business to a large event at Cloverleaf Fine Wine in Royal Oak. But as their business has grown, they’ve invested in their food truck – The Grindhouse – and in doing more charity events in town.

“[Last fall], we got to do a catered charity event which may be the thing I was most proud of,” Branch says. “At the Downtown Youth Detroit Boxing Gym, Rock Financial walked into the building with a check for $15,000. Catering has taken a step back to a point where we can do charity stuff.” They continue to work with Dave Mancini of Supino Pizzeria on efforts for the Gym, and last summer, Branch participated in the Next Urban Chef, a program that supports food education initiatives in the city.

While Branch contends they don’t want to overreach, he acknowledges that they’re primed for significant business growth. The USDA label will allow them to sell to local markets as well as take advantage of contacts across the western half of the state and the entire Midwest, building upon existing restaurant clientele in Cleveland and possibly Chicago.

So what comes next? Alexander showed me their new charcuterie cooler, which is in place though not fully built out. Within weeks, they should be hanging salumi and growing their cured meat portfolio. After, Branch says, “the next step will be provisions, like mustards.”

I pressed Branch a bit more about if all the work was worth it and if he’s still genuinely glad that he and Alexander chose to pursue sausage. He chuckled, and offered a sentiment that’s impossible to argue against: “Sausage is delicious. It’s delicious.”

Chicago Road Trip

In spring 2012, my alma mater, the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA) at the University of Michigan, printed two pieces I wrote after interviewing Chicago chefs and U-M alumni Rick Bayless and Stephanie Izard. They’re both being re-published here with permission of LSA Magazine.

In spring 2012, my alma mater, the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA) at the University of Michigan, printed two pieces I wrote after interviewing Chicago chefs and U-M alumni Rick Bayless and Stephanie Izard. They’re both being re-published here with permission of LSA Magazine.

If you have but one day in Chicago this summer, I can think of no finer way to spend it than lunching at Bayless’ XOCO and having dinner at Izard’s Girl and the Goat.

* * * * *

After graduating from the College of LSA, chef Rick Bayless spent years in Mexico studying the language, the people, the food. The knowledge he brought back to the United States helped change the landscape of cuisine as we know it. The linguistics major-turned-culinary-giant gave us a seat at the table to discuss his salad days – then and now.

Chef Rick Bayless (’75, M.A.) is every bit as infatuated with Mexican cuisine today as he was in 1987 when he opened Frontera Grill in Chicago and released his first book, Authentic Mexican: Regional Cooking from the Heart of Mexico. “I can look at something I discovered 30 years ago and understand it now in such an intimate way that I could never have done at the very beginning,” he says. “That sense of deepening discovery is what keeps me going every day.”

A recent winner of Bravo’s television program Top Chef: Masters and an unquestioned legend of Chicago’s now vibrant food scene, Bayless is as big a celebrity chef as anyone in the United States. It’s hard to imagine North Clark Street without his trio of restaurants or store shelves without his salsas, but he didn’t begin his career looking to be famous. Or even to cook.

“I was really interested in the relationship between language and culture,” he says of his college years spent studying Spanish and Latin American culture. After living in Mexico with his family as a teenager, Bayless became an undergraduate at the University of Oklahoma. He spent two summers in an applied linguistics program and learned how to enter communities that lacked a written language, learn and interpret their spoken words, and ultimately understand that culture through their stories.

He followed the program’s director to LSA’s Department of Linguistics, where he began several years of doctoral work. But he found more than just scholarly interests awaiting him in Ann Arbor.

“I fell in with this group of students… we didn’t have any money at all, but we were all super into food,” Bayless recalls. “I didn’t even understand how unique the food community of Ann Arbor was then, but it was centered around the farmers’ market.” He and his friends would buy their fresh ingredients in Kerrytown and at Eastern Market in Detroit, meeting and interacting with farmers, a practice reminiscent of the everyday life he’d experienced in Mexico.

These linguistics students prepared food together regularly, exploring different cuisines from a myriad of cultures. Bayless started catering. He taught local cooking classes. Then he had an epiphany: “I was at least as interested in the relationship between culture and food as I was culture and language.”

That’s when the future James Beard National Chef of the Year stopped work on his dissertation and immersed himself in the food of Mexico.

Throughout the early 1980s, Bayless lived and traveled in Mexico with his wife, Deann Bayless (’71, ’78 M.U.S.), utilizing his academic experience to construct Authentic Mexican. Each recipe was studied using the same research methodology he learned at Michigan: He prepared each dish with three different families or cooks to grasp every nuance, every approach, every ingredient. The result was more than a cookbook; it became a comprehensive look at the cuisine of Mexico as an expression of regional culture as well as an influential guide to a burgeoning American food scene that was slowly awakening from a decade or two of hibernation.

Upon returning to the United States, Bayless found himself in the midst of a dormant food culture dominated by commoditized products and corporate wholesalers – a stark contrast to his childhood.

“I’m a child of the ’60s. I made my first compost pile when I was 16. I made salt-rising bread,” he recalls. “I went with my father to the market in Oklahoma City… and the farmers would bring their stuff and we’d buy from the farmers,” Bayless remembers. “And then, that all went away and it just went to a commercial commodity market. We never had face-to-face contact with the people who were growing our food anymore. And I had a sense of loss about that.”

A do-it-yourselfer raised in a family of restaurateurs living amongst small farmers in Oklahoma, he couldn’t abide the lack of local food he found as he began his culinary career.

So Bayless set out to do things differently. He describes his first experience as a chef engaging Chicago-area farmers: “One of the things I wanted to do was put something local on our menu…. We opened in March, and May is when we have our short, local strawberry season… so I went down to the commercial market…. And they all said, ‘No one would carry those. They’re terrible.’ Well, they’re terrible only if you’re thinking of them as a commodity. They’re phenomenal if you’re thinking of them as flavor.”

Literally laughed out of the market by wholesalers, Rick and Deann drove twice per week to farmer stands outside the city to acquire those local berries for desserts. Beyond the superior flavor, the chef regained a connection to farmers in a way he hadn’t experienced since childhood. And he became increasingly grateful for it.

When Bayless talks about food, he looks and sounds as much like a professor of art history as he does a master of the culinary arts. His conference room at Frontera doubles as a library, its 10-foot walls lined with volumes on every conceivable culinary topic, ranging from French sauces to chocolate to Mexican culture to gardening. And, indeed, he broaches the subject of food as any intellectual might – that is, from every conceivable angle: flavor, art, community engagement, eco-friendliness.

Thus it’s perhaps unsurprising that his consistently calm demeanor elevates to a passionate tone when discussing the interrelated nature of his customers, his farmers, and his food.

“I have always seen restaurants – and I guess it’s because I grew up in a family-style restaurant—as creating community,” he says in describing his family’s approach to business. Along with those childhood trips meeting farmers, the notion of community has shaped his work.

“I’m an accidental organic farming champion,” he notes. “What I learned was that the people that cared most about what they were growing also cared most about the earth…. [Farmers] taught me about the interconnectedness of what I do as a living.” His holistic view of soil’s role in the food he serves his customers has led him to value sustainability. “If it’s local and sustainable, it’s part of that sense of community. It’s not just in putting money in the pocket of the farmer, but it’s protecting our environment that allows us all to thrive.”

Committed past the point of mere rhetoric or marketing, Bayless has maintained a laser-like focus: 25 years since he first ferreted out local strawberries, he has continued to push the boundaries of how local, sustainable food can be used. “The thing about food is that the more you’re around it, the deeper you can go,” he says.

During the late summer, 100 percent of his tomatoes and tomatillos are Chicago-raised. Even Tortas Frontera, his O’Hare Airport-based eatery, lists from where the food is sourced. His Frontera Farmer Foundation raised $180,000 last summer in support of local farms, and he’s a board member at the local Green City Market, the lone Chicago-area market dedicated solely to local, sustainable foods.

“With the strength of our local agricultural system, our food is different, and it allows a uniquely Chicago perspective on traditional Mexican flavor,” he says. So he strives to employ it often, noting that what he serves isn’t always what one might find in Oaxaca or the Yucatan. Rather, he asks himself, “How do you get local flavor on the plate without messing with the traditional soul that you find in Mexican kitchens?”

Bayless grows some of those Mexican-inspired ingredients on Frontera’s eco-friendly rooftop garden and at his own home. The only common ingredient that doesn’t occasionally come from Chicago-area farmers is dried chiles because, as he says, “the flavors just can’t be duplicated, and… we’re into making delicious food.”

In contrast to the many celebrity chefs leaving their hometowns, opening restaurants in Vegas or eating strange foods on cable television for shock value, Bayless’ three primary restaurants and offices are on a single block, and he’s entering the eighth season of Mexico – One Plate at a Time, airing locally in Chicago or on various PBS stations and often costarring his daughter.

When he does leave Chicago, it’s usually to visit other countries to study new cuisine and other cultures, and to enhance the culinary creativity on display at his restaurants.

“You can learn things that reflect back into your food, other techniques, and other ingredients that will open your mind to different flavor possibilities,” he observes. “Anything is open to us as long as it has the spirit of the Mexican kitchen.”

* * * * *

Chef Stephanie Izard has won Top Chef, not to mention a host of awards for her new Chicago restaurant, Girl and the Goat, but her food is neither haughty nor highbrow. Izard studies “common food” and elevates it, with a culinary result that’s like Izard herself – genuine and clever.

Soaked in syrupy lemon dressing, Chef Stephanie Izard’s eggplant is an eyeopening revelation. Eye-opening because it is a dessert; a revelation because it is the perfect acidic counterpoint to other elements on my plate: pork-fat doughnuts, ham streusel, caramelized figs, and a honey yogurt. Soft, crunchy, fatty, sweet, salty, and tart – it is an embodiment of Izard’s “make your whole mouth happy” philosophy.

The meals she prepares under that banner have garnered her and Girl and the Goat – the Chicago restaurant she opened in 2010 – national acclaim. Izard was a celebrity already, having won season four of Bravo’s wildly popular Top Chef, but it’s her work since, as chef and co-owner at the Goat, that have catapulted her to true stardom. Capturing rave reviews from the Chicago Tribune and Saveur magazine as well as a prestigious James Beard nomination, she was named a Food and Wine Best New Chef in 2011.

“If you could see me when I was on stage getting my award for that in New York, I had a gigantic perma-grin the entire time,” she recalls.

That’s hardly surprising: Izard’s a veritable ball of energy, talking fast, laughing a lot, and infusing every inch of her sizeable restaurant with every ounce of her sizeable persona. “I just wanted to take what I love about dining – which is hanging out with friends, usually quite a few drinks—and that’s why this place has a party vibe. Big fun with lots of energy.”

The space fosters that attitude with ample seating and high ceilings that echo with hundreds of voices, and a soundtrack that ranges from Johnny Cash to the Red Hot Chili Peppers to Regina Spektor. The bar is packed with tourists and regulars alike, and the atmosphere spawns conversation from the moment the front door opens.

Seated at the far end of that very bar, I was quickly befriended by a 40-something professional Chicagoan awaiting some friends. Within 45 minutes, I was sharing my cauliflower with pickled peppers and mint – portions at Girl and the Goat are naturally designed for sharing with friends both old and new – and she was sharing her goat chorizo flatbread.

The shareable, approachable food is just as driven by Izard’s demeanor as the palpable friendliness imbued throughout the dining room. Signature dishes like roasted pig face, a dramatically more interesting variation on traditional head cheese, elevate comfort food and ostensibly simple ingredients to haute cuisine, without even a hint of the snobbery that sometimes pervades the restaurant world.

“I’ve been lucky and have eaten at some amazing restaurants,” says Izard, “and I enjoy it, but I don’t enjoy the stuffiness of it.I just don’t think one has to come hand in hand with the other.” She adds, “I’ve definitely always been anti-pretense.”

That attitude is exemplified in her thorough, hands-on approach. Izard doesn’t just prepare a meal; she studies each component of it. Before opening the Goat, she took the time to visit local farms, getting to know the farmers and learning everything from how the animals are treated to how goat cheese is made. “Now [the farmers are] my friends. I call them up, we hang out,” she says. Izard contracts with farms “where we liked the farmers themselves and respect what they’re doing. We only get animals from farms where we know they’re raised properly.”

Her commitment to that depth of understanding extends to every aspect of the restaurant, which includes having an inhouse baker and butcher. She’s explored an interest in beer (the lone piece of art in the restaurant features a girl, a goat, and dancing beer bottles) by visiting Indiana’s Three Floyds Brewing and by actually making beer with Chicago-based Goose Island. “I’ve gotten to brew beer a couple times. I don’t think it’s anything I could do by myself, but it’s really cool to know more about it. And we make our own wine in Walla Walla (Washington). We make our own cheese. I just kind of want to learn how to do everything.”

Izard’s curiosity about food began early at her childhood home in Connecticut, where her parents enjoyed a wide range of cuisine. She earned a sociology degree from LSA in 1998, and if there were any hint at her future, it lay in evenings out with friends.”We would go through and order all these different beers, and I remember [learning] about it and thinking, “this is cool.'”

After graduation, she enrolled in Le Cordon Bleu in Arizona, where she learned the skills that later took her to several acclaimed Chicago establishments before opening her first restaurant, Scylla, in 2006. Despite rave reviews, she opted to close in 2008, not long after which she joined Top Chef. The prize money helped pave the way to her current endeavor.

From day one, Izard has insisted on staff sharing her excitement for their ingredients, drinks, and food.

From day one, Izard has insisted on staff sharing her excitement for their ingredients, drinks, and food.

“We interviewed over 1,000 people,” she says, “and we’ve interviewed people who worked at some of the best restaurants in the city, and I’m like ‘yeah, you’re a great server, but still, you’re not getting it. You need to have the enthusiasm, and you need to want to make someone feel comfortable as soon as they walk in the door.'”

Izard’s a master at lending that sense of comfort to her patrons: Sitting at the bar, looking toward the kitchen, I could see fans approaching her to say hi or take pictures, which often end up on the restaurant’s website. She’s become widely known for being one of the most sociable “celebrity chefs” in the country, someone who hasn’t changed as a result of her fame.”Even if I’m sick at the store and a fan comes up, I’m still going to talk to them. [Some chefs] get annoyed by people… but someone coming up to you and saying they love you? I mean, that’s pretty nice. Be happy about it.”

That connection with her devotees achieved new heights last summer when Izard launched a fundraiser for Share Our Strength, an organization fighting childhood hunger: “We’re doing these benefit dinners called Supper at Steph’s where I invite eight strangers into my house and cook dinner for them, and my staff said, ‘Seriously, Stephanie, what if they look through your underwear drawer?’ And I’m like, well, they’ll look through my underwear drawer. I don’t care.”

She’s laughing as a cook brings her a spoon covered in ginger dressing destined for the crunchy raw kohlrabi salad. “As long as I’m not in the bathroom, they’re supposed to bring me a taste.”

Izard’s well-known for carrying her upbeat persona and positive demeanor into the kitchen, a place notorious for hot tempers and demeaning attitudes. “I think that my cooks genuinely enjoy coming to work. Of course, they’re often hungover and tired and don’t really want to get here in the morning. But we have fun. We sing and dance all day. Having someone yell at me doesn’t make me want to work harder for them, it makes me want to have them not be around anymore.”

That’s not idle talk. The restaurant’s open kitchen allows patrons to peer inside. “You can see all the cooks smiling and enjoying each other’s company, which I just think is so important. If you’re putting out food that’s supposed to have all this love in it and you’re pissed off, it’s probably not going to taste as good.”

Her cooks must have an awful lot of love, because the lengthy menu is delicious from top to bottom. In her inimitable style, she doesn’t overthink it. “If I try too hard to make new menu items – like, all right, I must make a new fish dish this week, then it never works. So for me, it’s waiting to see if something just hits and something clicks. Like if I walk in the cooler and see some vegetable next to another one, and I’m like, ‘Yeah!'” That revelation explains her cross-cultural influences – for example, Izard’s crudo, an Italian-inspired raw fish dish, puts buttery Pacific hiramasa under bits of pork belly, Peruvian chiles, and caperberries.

That culinary creativity is showcased in Girl in the Kitchen, a book of recipes from her home kitchen released last October. She toured all winter to support the cookbook, while simultaneously planning her version of a classic diner, which she’s calling The Little Goat. She’s constantly busy, but she admits that’s how she likes it. “I’ve always been really driven and want to be as successful as possible. And I’m hoping to retire in 10 years, so I’ve got a lot to do.”

Lincoln Street

The first time I hung out at Lincoln Street Art Park was a couple of days before Halloween last year on a crisp autumn evening. The park’s founders were throwing a dedication party to celebrate the completion of the project’s first phase. We ate, drank, listened to tunes, and hung out around a pallet fire while the Amtrak Wolverine Service sped past a mere thirty feet away and a dazzling sundown filled the sky with orange and pink. It was a good day.

Subsequent impromptu bonfires saw us toasting ham and cheese sandwiches in a hobo pie maker or bidding farewell to winter by burning dried-up Christmas trees while Charley Marcuse, also known as Detroit’s singing hot dog man at Comerica Park, presented a speech rousing enough to complement the 20 foot high column of flames.

Pallet fires and trains and interesting people are enough to make a place appealing. At Lincoln Street, there’s also the art, from murals that cover entire walls to small ink drawings on random cinder blocks. There are graffiti tags, metal sculptures, stencils, and stickers. A frequent sightseer with a keen eye will find something new every time they visit. It’s a unique place, so I figured that more people should know about it and have the kind of fun I was having. With this in mind, Gourmet Underground Detroit organized our first event of the year – a late April potluck brunch.

Those who were paying attention to the Facebook event page chatter would have thought that the potluck was going to be a meatfest. And it was: Bob Perye from Rouge Estate was on hand with his smoker and more pulled pork than we could eat. He came armed with four different homemade sauces to complement the tender pork. He was also serving decadent slices of pork wrapped pork wrapped in pork, aka “FrankenBacon”, provided by Tim Idzikowski of Detroit BBQ Company. John Schoeniger of Porktown was grilling sauerbraten sliders while sipping on a fine German weisse bier. And someone even brought a party pack of Cajun fried turkey wings from the nearby Turkey Grill. This place has been on my radar for a couple of years now, but the potluck was the first chance I’ve had to taste the wings. They did not disappoint.

Those who were paying attention to the Facebook event page chatter would have thought that the potluck was going to be a meatfest. And it was: Bob Perye from Rouge Estate was on hand with his smoker and more pulled pork than we could eat. He came armed with four different homemade sauces to complement the tender pork. He was also serving decadent slices of pork wrapped pork wrapped in pork, aka “FrankenBacon”, provided by Tim Idzikowski of Detroit BBQ Company. John Schoeniger of Porktown was grilling sauerbraten sliders while sipping on a fine German weisse bier. And someone even brought a party pack of Cajun fried turkey wings from the nearby Turkey Grill. This place has been on my radar for a couple of years now, but the potluck was the first chance I’ve had to taste the wings. They did not disappoint.

Yes, there was an abundance of meat. But reflecting the diversity of Detroit, there was also plentiful vegetarian, vegan, and gluten free goodies. Assorted salads, pickles, savory tarts, guacamole, and sweets helped balance the spread. Everything was good, and I personally loved a simple cilantro, lime, and chickpea salad that spoke the language of a warm and sunny spring day in Detroit. Thanks to the generosity of Green Safe, there was no shortage of earth-friendly, compostable cups, plates, and utensils.

Yes, there was an abundance of meat. But reflecting the diversity of Detroit, there was also plentiful vegetarian, vegan, and gluten free goodies. Assorted salads, pickles, savory tarts, guacamole, and sweets helped balance the spread. Everything was good, and I personally loved a simple cilantro, lime, and chickpea salad that spoke the language of a warm and sunny spring day in Detroit. Thanks to the generosity of Green Safe, there was no shortage of earth-friendly, compostable cups, plates, and utensils.

As with any Gourmet Underground event, the libations were flowing. Evan Hansen revised a punch recipe to allow for single servings over ice that included three bottles of overproof rum. Assorted beer and wine was being poured from the tables, under the tables, around the tables. Towards the end of the day, the few of us that were still around and not wanting to let the day go were sipping Motor City Brewing Works hard cider with a float of corn liquor infused blueberries. Nobody went thirsty.

Lincoln Street Art Park won’t be mistaken for a typical suburban tract with plastic playground equipment and an acre or two of manicured lawn. Some rubble from the building that once stood on the lot still remains. A nearby hydrant has been leaking for so long that a small wetland habitat is growing around it and a sandpiper, typically a shoreline wading bird, has adapted to make Lincoln Street its home. It is the decaying Detroit that most of us know. But when the park is filled with the sounds of mirth, it is a Detroit that’s as alive as it ever was.

While we were cleaning up for the day and polishing off the last of that “City Billy hard cider spritzer,” Matt Naimi, in a moment of booze-fueled insight, best described Lincoln Street. He said, “we’re all just kids, and this is a great place to play.”

We dig Lincoln Street Art Park, and you should too. Show your love by voting for their proposed graffiti-style street art gallery in the Let’s Save Michigan Placemaking Contest.

We’ll see you at the 3rd Annual Belle Isle Potluck Picnic on Saturday, June 23.

RECIPES

Cilantro, lime, and chickpea salad

One 15-oz can chickpeas (2 cups cooked), drained and rinsed

2 cups spinach

1/4 cup sweet onion, chopped finely

Juice from 1.5 limes

3/4 cup fresh Cilantro

1/2 tsp sugar (or to taste)

2 tsp Dijon mustard

1 garlic clove

1 tsp extra virgin olive oil

1/2 tsp ground cumin

1/2 tsp kosher salt + ground pepper

Directions:

In a food processor, add the spinach and pulse a few times until chopped very small. Add the processed spinach, drained chickpeas, and chopped onion into a large bowl.

In the food processor (no need to rinse the bowl!), add the lime juice, cilantro, mustard, sugar, garlic, cumin, and oil. Process until smooth, scraping down the sides of the bowl as needed.

Pour the dressing on top of the spinach chickpea mixture and stir well. Add salt and pepper to taste. Let stand for about 10 minutes to let the flavors develop.

Bombay Government Punch (Hansen Remix)

3 bottles of Wray & Nephew overproof rum

3.5 quarts of cold-brewed Darjeeling tea

18 oz lime juice

16 oz demerara simple syrup

2 oz ginger syrup

Ideally, it’d be served on a block of ice so it slowly dilutes, and it’d go from being a bit too boozy and sweet to being pretty much perfect. But it was damn fine poured as single servings over ice.

On Gourmet

When Detroiters walk into Astro Coffee, it’s not uncommon to see a first-time patron walk up to the counter, look up at the menu, and say something like “I don’t want the gourmet coffee; what’s the regular one?” Or conversely, it’s easy to stroll the aisles of a supermarket and see trail mix, pasta, or hot dogs branded as gourmet products.

Context is everything. A word so over-utilized can only derive meaning from a group of people with a shared understanding of its meaning. It’s probably, then, the case that people who appreciate cuisine and its place in the world also can appreciate some elements of its history and even its lexicon.

Much like food and drink, language focuses a powerful lens on the unique aspects of a given culture. So it should be of little surprise that gourmet, one of our most enduring terms for describing those of discerning taste, is derived from French. It seems suitable that a country capable of producing burgundy and inventing Bearnaise should have coined a term for appreciation of delicacies that’s lasted almost 200 years and across languages.

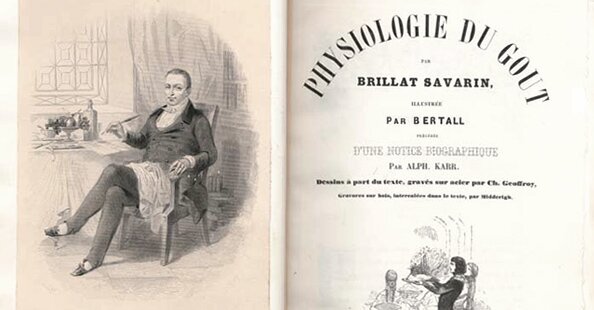

Perhaps the most well-known gourmet since the term came into popular usage was Jean Brillat-Savarin. His 1825 book The Physiology of Taste is widely regarded as the archetype for the contemporary food essay. Written in French and later widely translated, it was released only five years after the earliest use of the term in English as cited by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

Among his numerous opinions, Brillat-Savarin comes to the conclusion that “Those persons who suffer from indigestion, or who become drunk, are utterly ignorant of the true principles of eating and drinking.”

He’s drawing the distinction between gourmand and gourmet, between those who over-eat and those who enjoy quality. Interestingly, the former is a much older term: The OED cites an early written usage of gourmand in Vitae Patrum by English merchant William Caxton in 1495. While the two are often used interchangeably today, the two are, in fact, historically unrelated.

Derived from Old French words groumet and grommes meaning “manservant,” the term gourmet grew in Middle French to describe specifically the role of a wine valet, an attendant who understood the full range of wines’ properties. Such a servant was skilled, able to quite possibly discern a wine’s characteristics and origins from smell or taste.

While the OED hints that there may have been some earlier cross-pollination between Germanic languages and Old French, other sources are more confident in the connection. Some speculate that the root of the word groom, the Old English grōma (meaning a male child), was incorporated into the French language, initiating the evolution toward gourmet.

Of course, all that said, people were celebrating great food long before French aristocrats were training young men to sniff their wines for them.

Epicurus, the Greek philosopher, is the inspiration for English words epicure and, now, modestly clever combinations of words like “epicurious.” Today, Merriam-Webster defines an epicure as “one with sensitive or discriminating tastes,” a definition strikingly similar to that of a gourmet, though it also lists an archaic definition for one devoted to sensual pleasure.

It seems that this misconception of Epicurus as an unabashed hedonist emerged from something of a smear campaign against his name. While he is now widely acknowledged for having lived a modest life, his philosophy of simple, virtuous living leading to absence of pain or suffering was rooted in an atheistic worldview that eschewed an afterlife. Such thinking was clearly considered dangerous by many Christians throughout their own early history. Indeed, a derivation of his name came to be synonymous with heresy in early Christian cultures, and its earliest usages in English relate as much to religion as they do to food: Thomas Cooper, bishop of Winchester, lamented in his 1859 An admonition to the people of England that “The schoole of Epicure, and the Atheists, is mightily increased in these dayes.”

Still, throughout the 1600s and 1700s, his name was synonymous in some English-speaking circles with dainty, thoughtful consumption of delicious food, meaning that despite its confused origins, it pre-dates gourmet in its conveyance of this concept.

In the 20th century, though, there can be no doubt that “gourmet” came to symbolize all the finest things in the culinary realm. Even the magazine, Gourmet, that carried the term on its cover for seven decades is something of a metaphor for the word itself. When it debuted in 1941, Gourmet was the pinnacle of food magazines. While its primary competition was printed in black and white on newsprint with more modest recipes on its pages, Gourmet aimed to bring haute cuisine to its readers and itself embodied the spirit of the finer things, printed in color on glossier paper. Critics like James Beard reviewed restaurants in fashionable locales, and French cuisine was prominently featured.

But by the time the 90s came about, can anyone say that Gourmet carried itself differently than any other magazine? Scanning the shelves at a book store, it blended in among the dozens of new periodicals. Instead, it was larger, denser, more serious publications that came to earn respect, like Gastronomica or The Art of Eating. While Ruth Reichl, editor for the last years at Gourmet, managed to feature spectacular writing (look no further than getting David Foster Wallace to write about lobsters), the image of the magazine became confused: It sat next to bubble gum on store shelves, and in an effort to capture younger readers content was no longer solely aimed at the white linen crowd. Conversely, in its earliest history, there was a clear audience: It was reserved for those who cared and, frankly, probably those who had the means to care.

It’s a decent parallel. Just as the Gourmet brand saw itself diluted in a sprawling, re-emergent American food culture, the term gourmet has ostensibly lost its value with every package of preservative-laden, gourmet-labeled product that came to grace grocery store shelves. If everything is gourmet, then nothing is.

That said, with 200 years of history behind it, there’s still a case to be made for gourmet as a valued part of our cultural dictionary. After all, in context, it still has meaning. And among people who do truly care about what they’re eating, it can retain that meaning, the one and the same about which Brillat-Savarin wrote 200 years ago. At the very least, I’m sure everyone can agree it’s more appealing and more appropriate than foodie.

Commitment to the Vine

Two Cavas were poured, side by side – one a venerable, well-known producer, the other a relatively unknown label, new to the U.S. market. We stuck our noses into our glasses, tasted each, and ultimately agreed that the latter was fruitier and more pleasurable. That sort of intense expression of natural fruit is a hallmark of Ferndale’s Vinovi & Co., a new boutique importer specializing in Franco-Iberian wines.

My hosts that afternoon were Núria Garrote i Esteve, owner and driving force behind Vinovi, and her husband, Elie Boudt, proprietor of Royal Oak’s Elie Wine Company. We were drinking Cava Vall Dolina, one of the company’s initial offerings.

Núria is a mechanical engineer by day, tending to her nascent business over lunch, at night, and during weekends. Born in Catalunya, the culturally and historically distinctive region of Spain around Barcelona, she is in many respects the perfect candidate to build an importer of Spanish wines: She’s familiar with the culture, the language, and the wines. And it so happens, the 37-year-old business owner is born of the same generation as most of the winemakers she represents.

“You cannot relate winemaking to the old guy that is on the farm anymore,” Núria says. She recounts one of the first building blocks for her business, a series of meetings in Barcelona four years ago. While the formal program showcased larger brands, informal side gatherings were commonplace, and it was there she began to identify potential partners: “I said to Elie, ‘Do you realize that like 80% of these winemakers are from my generation?”

That many of the winemakers in her portfolio are young is perhaps surprising. Arguably more intriguing, though, is that this group is re-embracing the tradition of winemaking from its very roots – farming.

“The producers, what they do, is that they are hands-on in the vineyard,” Núria explains. “That’s why you get the intensely fruity, aromatic wines. They pay attention to the vines, they harvest at the right time, and then they don’t overdo it with the wood [barrels].”

I found it compelling to hear her speak so passionately about what younger generations are doing in Spain since it ostensibly parallels what’s happening with urban farms, upstart food companies, craft cocktails, and other aspects of the American food movement: Young people are going back to traditions long past and creating authentic, new products.

As Núria was striking out across her homeland looking for these types of producers, she had three elements in mind: uncommon vines and varieties, emerging areas that have been historically overlooked by other importers, and people who were attempting to redefine classic styles.

Starting with a clear philosophy has obvious selling points, but it also means that from a practical business angle, Núria was starting from something of a disadvantage. “It seems to be obvious, but it’s not that easy to find producers who are committed to their land,” she laments.

That commitment tends to be found in fairly tiny operations. Small production, though, isn’t always an indicator of quality. It can’t be a stepping stone to a drastically larger operation. Rather, it has to be a consequence of focus and drive to make a heartfelt wine. That Núria’s producers focus on farming – the dirty, difficult work that is the source of every bottle we drink – is a telling sign.

But how did she secure the business of these farmers and winemakers? First, she had to find them. “[These wines,] you cannot even buy them in Barcelona,” she says, noting that all these producers are very tiny. Their products are often bought up by a handful of fashionable restaurants or may even stay within their immediate regions.

As her husband Elie pours two glasses of red for each of us, he chimes in on some of the challenges in building a relationship with these types of winemakers.

“I used to listen when customers would say to me and say ‘Oh yeah, the best stuff from Italy stays in Italy, or the best stuff from France stays in France.’” As a shop owner, he initially thought it a bit naïve. But now, he concedes, “there’s a grain of truth to it. When we talk to these people who make small amounts, they want to keep it around.”

Noting that many of the producers they’ve met in Spain want to earn the respect of their peers and their regional customers, he elaborates, “If he sends everything he makes to Detroit, we have the market to sell it, but they’re looking for that local echo.”

However, they’re also looking to make a living and to acquire the prestige that comes from being in the U.S. market.

It’s a bit of a paradox, but that’s where Vinovi & Co. has been able to connect with these Spanish winemakers. As a native who speaks Catalan and Spanish, as well as French and English, Núria was able to establish a rapport with producers hesitant to export or who were interested in the U.S. market only with the support of a trusted importer.

Elie returns from checking on their daughter and notes that several of Vinovi’s potential producers were also concerned about the United States’ penchant for heavily manipulated wines aimed at getting big scores with popular wine critics. He motions to our glasses, pointing at Alcor – a rich, food-friendly wine made from a blend of both native and non-native grapes in Catalunya – and said, “he wasn’t even interested in coming to the U.S.”

Núria mentions that the other wine we’re drinking, Sot Lefriec, was imported by a different company and scored well with the U.S. press. But the winemakers were unhappy. Speaking more generally, Núria continues, “They’re not going to bring their wines here to have them sit in Virginia in a warehouse… but if they feel like they have the right importer, well, we didn’t have any problems.”

Traveling to Spain 4 or 5 times each year, she’s in touch with her winemakers often. And she maintains trust by keeping a close eye on their products: “I keep everything temperature controlled when I bring it on the boat to all the way when it gets here.”

Beyond that, Elie underscores the importance of her multi-lingual background – the insight it provides. “People ask me why I specialize in French and Spanish wine, and I say ‘because that’s all I can wrap my mind around.’ I have to know the culture, the language, and everything that really contributes to what the wine is.” He continues, “I’m not saying I’m an expert, but I’m always learning all these things. I mean, here I am and I don’t speak Spanish, but I’m hoping to do so.”

Quickly, Núria interrupts, “Ha! We’ll toast to that!”

Jokes aside, that simple conversational ability is an important foundation. Núria’s work on the other side of the Atlantic was “a lot of visits, a lot of reading, but a lot of conversation, you know?” But she never forgot her principal commitment to farming, “Every time visiting the vineyard, not necessarily the winery. We don’t pay much attention to the winery – but the vineyard. And to the people.”

Those people are a diverse, interesting lot. And they produce a diverse, interesting group of wines.

That fruity, dry, biscuity, bright, delightful Cava we were drinking, Vall Dolina’s Naturally-Brut Reserva, was made by two men in their early 30s using organic farming methods with vines about 25 years of age – one of only a few “grower Cavas” available. She imports a beautiful, edgy, dry Riesling, Ekam, from Raül Bobet, an outspoken winemaker with a PhD in chemistry who spends his weekends tending to what Núria believes may be the most elevated vineyards in Spain. Then there’s the expatriated Englishwoman Charlotte Allen, whose brand “Pirita” is named for the Spanish word for pyrite, so abundant in the relatively barren soil of her western frontier vineyards that the ground shimmers.

Some of these wines are treated to oak; others are fermented in 12th-century stone vessels. Some are raised in heirloom plots; others are grown in inhospitable areas that have gone virtually ignored by other winemakers. But all of these wines are vinified by growers who care about their crops, harvesting by hand from vines with low yields.

Núria searched for years to find these producers and their wines, but surprisingly – to me, at least – there weren’t many bureaucratic hurdles stateside.

“Nothing was difficult… It’s lengthy in terms of time and if you go in blind and you underestimate their procedure, you’re gonna fail. But there are manuals online for everything. It’s a matter of knowing what it takes and just following.” she reveals. That’s not to say everything always goes smoothly: Núria has been waiting for about six months for Michigan to approve the label for a product that she’s hoping to debut in metro Detroit this spring.

They open a wine that they hope will be available in a couple of years – Pirita Blanco. Ripe but explosive, it’s a beautiful, balanced wine, and like her red, it’s made from indigenous, unheralded grape varieties and fermented using native yeast.

This bottle prompted Núria to relay a quick story about the winemaker and the nature of her tiny, remote operation. “She came driving a car with a French plate because she had lived in France,” Núria continued, “and she was speaking English because she’s British. People in town there are very isolated, mostly old people. So they call her la francesa, which is ‘the French woman,’ because they recognize the plate but they don’t recognize the English language.”

I’ve purchased some of Núria’s wines from Elie’s shop in Royal Oak, including a few bottles of Pirita, but I asked how business has been going otherwise. Thus far, she’s brought in more than 25 pallets totaling about 15,000 bottles of wine, and of the 17 labels currently in her portfolio, many of them have been placed in local restaurants.

In particular, she cites Joseph Allerton of Roast (Detroit), Christian Stachel at Café Muse (Royal Oak), and Antoine Przekop of Tallulah Wine Bar and Bella Piatti (Birmingham) as sommeliers who have embraced her approach.

Retail customers looking to try her wines will find a wide array of prices – from around $10 to upwards of $100. “The price structure was not intentional at all,” she explains. But in cases where she was genuinely interested in a winemaker that made multiple wines, she was careful to select at least one that fit lower prices.

Of course, as Vinovi & Co. grows, its pricing structure is bound to change. And while Núria intends to retain her principled approach, plans to move beyond Spain are already in process: She’s working with winemakers in France and Portugal to bring in their products, hopefully as soon as this year.

Regardless of what the future holds, don’t expect Núria’s approach to change. She’s after quality that comes from commitment, and there’s no way to fake that: “You look for small production, hands-on in the vineyard, and a strong personality putting a vision into what they do.”

___

Vineyard and winemaker photos courtesy of Núria Garrote i Esteve.

A Genuine Slice

Master pizzaiolo Dave Mancini’s move from a comfortable career as a physical therapist to serving what is arguably the best pizza in Detroit has been well documented. But it was no easy journey. It took hard work, passion, persistence, and an enduring love for the city to make it happen.

“You can’t hide behind the cheese”

What makes Supino pizza so good? It isn’t some flawless recipe handed down by Mancini’s Italian ancestors or discovered in an ancient Roman text. The secret to his success is nothing more than a focused effort to make the best possible pizza that he could. In fact, it took about seven years from the time he started making pizza to the eventual opening of Supino.

“I researched the shit out of pizza,” he says. To learn the business model, on his Saturdays off, he worked in a Birmingham pizzeria. He bought every recipe book he could find, even purchasing entire books for just one pizza recipe. After struggling with a few variables in the crust that he just couldn’t get a handle on, he did some consultation with a former pizzaiolo at Boston’s renowned pizza joint, Santarpios, until he got the consistency that he was looking for.

“A pizza is never really better than its crust. You can have amazing toppings and amazing sauce but if the crust is mediocre, the pizza is going to be mediocre.”

Regular patron and pizza aficionado, Phil Spradlin, tends to agree. He only orders his pizza with cheese because, as he tells Mancini, “You can’t hide behind the cheese.”

Regular patron and pizza aficionado, Phil Spradlin, tends to agree. He only orders his pizza with cheese because, as he tells Mancini, “You can’t hide behind the cheese.”

The question of style comes up more often than Mancini would care to address. “It cracks me up when I hear ‘New York-style pizza and New Haven-style pizza’, he says. “There are so many variations within those subgroups. Even between those two there is overlap. If you go to New York and get pizza at six different places, they are going to be pretty damn different. They’re not going to be Detroit-style, like Buddy’s, or Chicago-style. You can probably find those in New York but when people talk about New York-style pizza they aren’t pinning down a specific process. Most of them have a thin crust and are 18-inch pies but other than that, they’re kind of their own thing.”

He gets New Yorkers that come into the shop with a broad range of opinions. Some of them will tell Mancini that the pizza is just like home, some of them will tell him that it’s not really like home but it’s good enough, and some of them will tell him that it’s better than home.

Ask Mancini what style of pizza he makes and the short answer is “Dave’s style”.

Detroit Synergy

Local media make a big deal when celebrity chefs open upscale restaurants in Detroit. These successes certainly foster a positive perception of dining in Detroit, both locally and nationally. But it’s just as crucial – some would say even more so – for the resurgence of the city that small, independent establishments take root in their respective communities and be more than simply a place to eat good food.

For Mancini’s part, he’s doing what he can to help other promising food businesses by using their products and sometimes even opening his kitchen to them. You can order Katie’s Cannoli, hand-filled at the time of order so the shell stays crisp, for dessert. Porktown trades a portion of their sausage for use of his kitchen and Mancini purchases more for his pizza. The Asian inspired pop-up café, Neighborhood Noodle, operated out of Supino for a few of their monthly gigs.

He seems almost embarrassed talking about the role he plays in this culture of cooperation, and believes he sometimes gets too much credit. Mancini recognizes that he’s certainly not the first one to think of mentoring other food entrepreneurs and is quick to praise those that have come before him and have helped him get his own business off to a strong start.

He seems almost embarrassed talking about the role he plays in this culture of cooperation, and believes he sometimes gets too much credit. Mancini recognizes that he’s certainly not the first one to think of mentoring other food entrepreneurs and is quick to praise those that have come before him and have helped him get his own business off to a strong start.

Like Jerry Belanger, owner of Park Bar, who would come in and order fifteen pies to hand out to his customers and give Supino a boost in its early days after opening. Spirited restaurateur Torya Blanchard helped to get Supino featured in Delta Sky Magazine. When Mancini decided he wanted to serve beer, Dan Scarsella of Motor City Brewing Works consulted with him, knowing the two businesses might be in direct competition.

Even neighboring Russell Street Deli would hand out menus to their customers during the lunch hour, apparently unconcerned about the possibility of losing customers. Mancini maintains that this cooperative culture “especially plays well in Detroit, because we’re underserved”.

He recalls the recent food truck gathering in Shed 2 of Eastern Market and how he was slammed with customers the entire time just because the event drew hordes of hungry people. Though some of his friends in the restaurant industry bristle about the possible competition with food carts, he believes that Detroit is a long way away from worrying about this kind of rivalry for the dining dollar.

Eastern Market on the rise

Eastern Market wasn’t the first location Mancini thought of when looking for a building to house Supino’s kitchen. It was only after an extensive three-year search, underscored by negotiations with indifferent landlords that had no interest in taking any risk by repairing the spaces they owned, that he “fell backasswards” into his current location.

Mancini finds far more advantages than challenges being based out of the Market district. Though all the buildings are old and there is always something that needs repair, that’s more than made up for by the steady foot traffic from the Saturday market, folks from downtown coming in for lunch on the weekdays, and other food workers in the neighborhood. “I think people with a good food idea are crazy not to jump into the Eastern Market area,” he says. He especially thinks that a good bistro and brewpub would do well there.

Mancini has no plans to open a new location any time soon. He’s not the type to risk the quality of his product to cash in on its popularity. But there will be some changes this year.

Mancini has no plans to open a new location any time soon. He’s not the type to risk the quality of his product to cash in on its popularity. But there will be some changes this year.

He is consulting with local drinks authority, Putnam Weekley, to bring in a beverage program. Soon you’ll be able to order a beer or inexpensive glass of table wine chosen specifically to pair with the pizza. He also envisions a small, European-style bar with plenty of apertivi, digestivi, and a modest liquor selection. He speaks enthusiastically about Amaro CioCiaro, a bittersweet Italian liqueur produced in the same region as the town of Supino, Italy that he noticed one night while drinking at The Sugar House.

But instead of rushing to sell booze and maximize profit, he’s carefully planning how and what to introduce into the menu and ensure the core of his business stays healthy. While unsexy in comparison to a San Gennaro pie straight from the oven, all of this methodical planning and attention to detail is fundamental to Dave Mancini’s success, and makes certain that Supino will remain a fixture in Detroit for a long time to come.

Season’s Greetings

Has there been, in recent memory, a better Detroit holiday season for food lovers and gluttons than this December? Hackneyed as the sentiment may seem, this has already been a pretty joyful, stirring month.

There was pleasure and even inspiration to be had from watching people coming together for the 2nd annual Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar and from talking to people who were just discovering that interesting things are happening with food in Detroit. And it was legitimately fun to see old friends hanging out, new friends being made, and small business owners connecting with one another over pickled turnips and tequila at the Sugar House.

The sentimental fool in all of us has to derive some sense of satisfaction from watching much of Detroit’s gastronomic community enjoy not just each other’s products but each other’s company.

That’s all a long way of saying that the holiday season is off to as fine a start as one could hope for.

In case you missed either event, we’ve put together a little slide show of both, which begins with a special holiday greeting card, Gourmet Underground Detroit style. Best wishes for a wine-soaked end to 2011 and a pork-filled 2012.

The Science & Art of Espresso

A moment or two after sliding the lever on his Synesso espresso machine to the left, a rich, dark, wood-toned liquid poured from the two opposing spouts at the bottom of the portafilter and ran smoothly into the tiny cup below. Staring at it intently, Dai Hughes commented, “It’s ideal when it pops out and hugs back in a bit, so it kinda gets that hourglass shape. It’s a very feminine shape it’ll take on.”

Dai, owner of Corktown’s Astro Coffee, is describing the appearance of his ideal espresso, a particularly rich, saporous shot. Whereas a traditional, Old World barista may aim, no matter the bean, for a fairly consistent bitterness and flavor, Dai and his contemporaries are generally striving to emphasize unique flavors within particular blends and beans.

Espresso is a finicky product, and I had been curious how he goes about crafting what is arguably the best tasting espresso in southeast Michigan. He invited me behind the counter to get a first-hand look.

Before pulling that first shot, Dai describes the myriad variables at play. “When I started [as a barista], our parameters were the coarseness of the grind, the dose, and the tamp [of the grounds in the filter],” he says. “Then we introduced controlling the temperature. And what people were saying is that machines were set at their golden temperature… but what if beans were suited to different temps?”

Today’s routine actually begins with that adjustment. “I’m using the Owl’s Howl, which is the last thing I used the last time we closed, so there’s at least some familiarity,” he says, referring to having a recent reference point to the beans he’s placed in the grinder. We peer underneath the three-headed espresso machine to see the temperature controls. He left the day before with the temperature set to 200.5 degrees. Thus to get an idea of the flavor within a wider range, he sets the first group to 200 and the second to 201.

After running several doses of beans through the grinder to clear it of the previous day’s now-oxidized coffee, he runs the first shot, which we won’t bother to taste, and looks to see if it runs out of the machine with that hourglass shape. Before measuring a single thing, he’s both seasoning the machine and checking to see if he’s near that ideal viscosity. We’re in the ballpark, but, he notes, that’s not always the case: “You can come in, especially if you’re switching to a new espresso, and the thing is just pissing out or it’s ‘drip, drip, drip.’”

Dai grinds another dose and puts it on the scale. His first measurement shows the grounds weigh just over 17g. He makes a shot and measures the resulting liquid at over 27g.

“I’m collecting information at this point,” he says, “but we’ll taste this one to understand where we’re at.” We taste it, and it’s thin. He pulls another at the higher temperature, and it seems as though it may be thicker in body but definitely more astringent.

The grounds for our third shot weigh in at 19g, he sets the temp back to 200.5, and the shot itself comes in at around 25.5g – a dry-to-wet comparison of about 74 or 75%, which is closer to Dai’s ideal range. It’s delicious.

For many baristas, these types of ratios and measurements guide the ideal shot. This is an area where Dai has a philosophical difference with many of his fellow baristas: At this point in the process, he’s starting to let his experience and his taste buds drive the decision making. He’s after a balance of fruit and acidity – an explanation which elicits a grin from me because it’s a concept to which anyone that has made a cocktail or uncorked a bottle of cru Beaujolais can relate.

“Part of it is knowing that things can change… especially right at the beginning. Temperatures are changing, the door is swinging open, it’s hot, it’s humid,” he laments. But in this case, without even adjusting the grinder, the dosing of his grounds has settled out at a dry weight of 19g. He tweaks the temperature again, up to 200.7 degrees, and we try another shot.

“Part of it is knowing that things can change… especially right at the beginning. Temperatures are changing, the door is swinging open, it’s hot, it’s humid,” he laments. But in this case, without even adjusting the grinder, the dosing of his grounds has settled out at a dry weight of 19g. He tweaks the temperature again, up to 200.7 degrees, and we try another shot.

This one is, to Dai’s taste, pretty much ideal. The flavor is true to his objective – ripe, berry-ish, thick, and a bit tart. But he emphasizes that others may prefer the shot pulled at 200.5 degrees instead. Or even something else entirely. And of course, he notes, the prevailing opinions among coffee wonks everywhere change frequently: “There was a period of time when over-dosing was cool… and you do a coarser grind with more in it. But… this is going to change in three months. Someone will have written a new guide.”

Even the parameters of what baristas can control are in flux. In addition to grind, dose, temperature, and so on, companies have introduced machines with pressure controls. “Then the pressure profiling systems came, and you just have so many parameters,” he says with a bit of skepticism.

For Astro, the constant is ostensibly Dai’s sense of taste.

“We’re dialing in to this range of comfort, and from there, the micro-adjustments – temperature or, at times, grind on the collar [of the grinder] and things like that – we’re going to make those on the fly and then taste. It’s good to know these other kinds of things, but it’s good to taste. You can have all the ratios in the world, but there are all these other factors.”

Dai honed his skills – and his taste buds – at London’s Monmouth Coffee, an early pioneer in today’s culture. “Coffee culture is really young… but it has changed so rapidly in the last 5 to 10 years. So what you see here, it wasn’t like this at all.” Still, founded in 1978, Monmouth practically invented the concept of “direct trade,” and Dai – admittedly a coffee neophyte before he began working there – got his start in that knowledgeable environment.

Having experience from an older, established shop seems to offer him perspective: “Imagine if you were apprenticing as a brewer,” he posits, “what they teach they might also tell you is the law or the only way to do it. But it’s not. Have you ever had two IPAs that are exactly the same? No. And if I order a shot somewhere else, I don’t want it to taste exactly like mine.”

Rather than touting the next big machine or adhering to the newest geekery-inspired guidelines, he seems focused primarily on giving customers a pleasant experience and letting his expression of the innate, delicious flavor of his product do the talking.

He motions toward the four espresso cups from which we’ve tasted and says, “You’ve probably tasted all those shots in your life – or even just here. Underextracted, overextracted… an espresso is the highest error drink we can do. At some point, put your books away, put your refractometers away. This is something, like wine, that’s constantly changing.”

We finish tasting that final shot and he adds, “I don’t think you can truly enjoy it until you respect that.”

Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream

If you’ve followed Gourmet Underground Detroit for any length of time, you know that one of our favorite seasonal cocktails is Bourbon Milk Punch. It has qualities similar to eggnog without being thick and cloying, thus easier to consume multiple drinks if one is so inclined, as we usually are. Earlier this year, we suggested to Scott Moloney, owner and operator of Treat Dreams, that he turn this handsome drink into an ice cream flavor.

No amateur when it comes to crafting ice cream out of unorthodox (and occasionally bizarre) ingredients, Moloney was initially inspired to push boundaries after seeing the “challenging” San Francisco ice cream shop, Humphry Slocombe, make a prosciutto ice cream. Among his recent, most peculiar projects is a brown sugar ham ice cream that acquired its flavor from simmering the ice cream base with a ham bone and clove. In the works is a Thanksgiving layered concoction built with one part turkey ice cream, one part sweet potato ice cream, and one part cranberry ice cream.

No amateur when it comes to crafting ice cream out of unorthodox (and occasionally bizarre) ingredients, Moloney was initially inspired to push boundaries after seeing the “challenging” San Francisco ice cream shop, Humphry Slocombe, make a prosciutto ice cream. Among his recent, most peculiar projects is a brown sugar ham ice cream that acquired its flavor from simmering the ice cream base with a ham bone and clove. In the works is a Thanksgiving layered concoction built with one part turkey ice cream, one part sweet potato ice cream, and one part cranberry ice cream.

Ice cream flavored with alcoholic beverages seem mainstream in comparison.

Moloney has done plenty of liquored-up ice cream flavors before this project, as demonstrated by a well-stocked bar in the Treat Dreams kitchen. He has used beer, wine, mead, vodka, absinthe, Chambord, and lots of bourbon. He instructed us on just how much booze we could legally add — to a total of 4% by volume — and we went to work trying to replicate the flavor profile of the drink.

Moloney has done plenty of liquored-up ice cream flavors before this project, as demonstrated by a well-stocked bar in the Treat Dreams kitchen. He has used beer, wine, mead, vodka, absinthe, Chambord, and lots of bourbon. He instructed us on just how much booze we could legally add — to a total of 4% by volume — and we went to work trying to replicate the flavor profile of the drink.

The finished ice cream contains a healthy amount of Buffalo Trace Bourbon as the base flavor, a touch of St. Elizabeth’s Allspice Dram for a spicy and mildly bitter flavor kick, and a dose of fresh nutmeg for dreamy, floral aromatics. Success! It definitely tastes like the milk punch we make at home – which means it’s damn good.

The release of Treat Dreams’ Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream coincides with the opening of Planet Ant Theatre’s upcoming play, The Sunday Punch, a comedy that “explores the bewildering journey through aging, marriage, and family roles, while addressing the dangers of apathy and silence in the face of injustice”. Gourmet Underground wholly supports the arts and we figured this was as good a reason as any to finally bring life to this ice cream flavor.

The release of Treat Dreams’ Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream coincides with the opening of Planet Ant Theatre’s upcoming play, The Sunday Punch, a comedy that “explores the bewildering journey through aging, marriage, and family roles, while addressing the dangers of apathy and silence in the face of injustice”. Gourmet Underground wholly supports the arts and we figured this was as good a reason as any to finally bring life to this ice cream flavor.

Since Treat Dreams opened a little over a year ago, the energetic Moloney has carried out dozens of these promotional collaborations with other independent businesses. He’s used everything from nearby Pinwheel Bakery cinnamon rolls to Slows brisket to create local flavors and he obviously enjoys working with his fellow small business entrepreneurs. While some of these flavors might not have the mass appeal of vanilla and chocolate, it’s certain that anyone can find something to his or her liking at Treat Dreams. We wouldn’t be surprised if it were the bourbon milk punch.

Treat Dreams is open 1 p.m.-9 p.m. Sunday through Thursday, and 1 p.m.-10 p.m. Friday through Saturday. Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream will be available for purchase starting Friday, November 25th to correspond with the opening of The Sunday Punch at Planet Ant Theatre Hamtramck.

Eventually, they’re hoping to employ a seasonal approach to the menu, changing drinks more frequently and exposing people to more options and more ideas. For the time being, they’re taking their role as educators seriously. Between shaking drinks, Aversa chimes in, “We do a lot of talking with our guests, a lot of brainpicking. Asking people what they’ve had before.”

Eventually, they’re hoping to employ a seasonal approach to the menu, changing drinks more frequently and exposing people to more options and more ideas. For the time being, they’re taking their role as educators seriously. Between shaking drinks, Aversa chimes in, “We do a lot of talking with our guests, a lot of brainpicking. Asking people what they’ve had before.”