GUD FEATURE ARTICLE

On Gourmet

When Detroiters walk into Astro Coffee, it’s not uncommon to see a first-time patron walk up to the counter, look up at the menu, and say something like “I don’t want the gourmet coffee; what’s the regular one?” Or conversely, it’s easy to stroll the aisles of a supermarket and see trail mix, pasta, or hot dogs branded as gourmet products.

Context is everything. A word so over-utilized can only derive meaning from a group of people with a shared understanding of its meaning. It’s probably, then, the case that people who appreciate cuisine and its place in the world also can appreciate some elements of its history and even its lexicon.

Much like food and drink, language focuses a powerful lens on the unique aspects of a given culture. So it should be of little surprise that gourmet, one of our most enduring terms for describing those of discerning taste, is derived from French. It seems suitable that a country capable of producing burgundy and inventing Bearnaise should have coined a term for appreciation of delicacies that’s lasted almost 200 years and across languages.

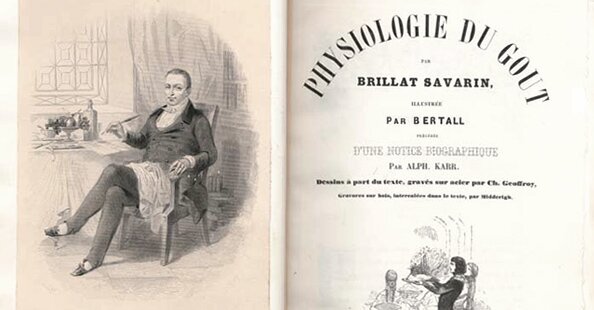

Perhaps the most well-known gourmet since the term came into popular usage was Jean Brillat-Savarin. His 1825 book The Physiology of Taste is widely regarded as the archetype for the contemporary food essay. Written in French and later widely translated, it was released only five years after the earliest use of the term in English as cited by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

Among his numerous opinions, Brillat-Savarin comes to the conclusion that “Those persons who suffer from indigestion, or who become drunk, are utterly ignorant of the true principles of eating and drinking.”

He’s drawing the distinction between gourmand and gourmet, between those who over-eat and those who enjoy quality. Interestingly, the former is a much older term: The OED cites an early written usage of gourmand in Vitae Patrum by English merchant William Caxton in 1495. While the two are often used interchangeably today, the two are, in fact, historically unrelated.

Derived from Old French words groumet and grommes meaning “manservant,” the term gourmet grew in Middle French to describe specifically the role of a wine valet, an attendant who understood the full range of wines’ properties. Such a servant was skilled, able to quite possibly discern a wine’s characteristics and origins from smell or taste.

While the OED hints that there may have been some earlier cross-pollination between Germanic languages and Old French, other sources are more confident in the connection. Some speculate that the root of the word groom, the Old English grōma (meaning a male child), was incorporated into the French language, initiating the evolution toward gourmet.

Of course, all that said, people were celebrating great food long before French aristocrats were training young men to sniff their wines for them.

Epicurus, the Greek philosopher, is the inspiration for English words epicure and, now, modestly clever combinations of words like “epicurious.” Today, Merriam-Webster defines an epicure as “one with sensitive or discriminating tastes,” a definition strikingly similar to that of a gourmet, though it also lists an archaic definition for one devoted to sensual pleasure.

It seems that this misconception of Epicurus as an unabashed hedonist emerged from something of a smear campaign against his name. While he is now widely acknowledged for having lived a modest life, his philosophy of simple, virtuous living leading to absence of pain or suffering was rooted in an atheistic worldview that eschewed an afterlife. Such thinking was clearly considered dangerous by many Christians throughout their own early history. Indeed, a derivation of his name came to be synonymous with heresy in early Christian cultures, and its earliest usages in English relate as much to religion as they do to food: Thomas Cooper, bishop of Winchester, lamented in his 1859 An admonition to the people of England that “The schoole of Epicure, and the Atheists, is mightily increased in these dayes.”

Still, throughout the 1600s and 1700s, his name was synonymous in some English-speaking circles with dainty, thoughtful consumption of delicious food, meaning that despite its confused origins, it pre-dates gourmet in its conveyance of this concept.

In the 20th century, though, there can be no doubt that “gourmet” came to symbolize all the finest things in the culinary realm. Even the magazine, Gourmet, that carried the term on its cover for seven decades is something of a metaphor for the word itself. When it debuted in 1941, Gourmet was the pinnacle of food magazines. While its primary competition was printed in black and white on newsprint with more modest recipes on its pages, Gourmet aimed to bring haute cuisine to its readers and itself embodied the spirit of the finer things, printed in color on glossier paper. Critics like James Beard reviewed restaurants in fashionable locales, and French cuisine was prominently featured.

But by the time the 90s came about, can anyone say that Gourmet carried itself differently than any other magazine? Scanning the shelves at a book store, it blended in among the dozens of new periodicals. Instead, it was larger, denser, more serious publications that came to earn respect, like Gastronomica or The Art of Eating. While Ruth Reichl, editor for the last years at Gourmet, managed to feature spectacular writing (look no further than getting David Foster Wallace to write about lobsters), the image of the magazine became confused: It sat next to bubble gum on store shelves, and in an effort to capture younger readers content was no longer solely aimed at the white linen crowd. Conversely, in its earliest history, there was a clear audience: It was reserved for those who cared and, frankly, probably those who had the means to care.

It’s a decent parallel. Just as the Gourmet brand saw itself diluted in a sprawling, re-emergent American food culture, the term gourmet has ostensibly lost its value with every package of preservative-laden, gourmet-labeled product that came to grace grocery store shelves. If everything is gourmet, then nothing is.

That said, with 200 years of history behind it, there’s still a case to be made for gourmet as a valued part of our cultural dictionary. After all, in context, it still has meaning. And among people who do truly care about what they’re eating, it can retain that meaning, the one and the same about which Brillat-Savarin wrote 200 years ago. At the very least, I’m sure everyone can agree it’s more appealing and more appropriate than foodie.

2012.04.23 Evan Hansen at 7:46 am

This entry was posted in Features and tagged food, France, history. Bookmark the permalink.

One Response to On Gourmet

Pingback: On Gourmet | Gourmet Underground Detroit « The Net Gourmet